Steve Lau, Chair of the Ensuring We Remember Strategic Partnership Board, shares the story of an inspiring encounter with men from Shandong on a recent visit to China.

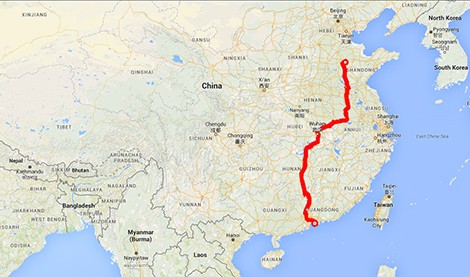

Three hours before I was due to take off, my plans to fly from Jinan to Shenzhen were scuppered. I won’t explain why, not because it would take too long, but because the tale, to be honest, is a tedious one. I decided I would take the train, despite the fact that it would add twenty hours to the original three hours the flight would have taken. But a soft-sleeper berth would mean the journey would be comfortable and pass quicker than the timetable suggested.

Anyone who has purchased a ticket at a Chinese railway station will know that it can be something of an ordeal. Fortunately I avoided the usually unavoidable stand in an extremely long queue, (a queue that you can never be absolutely sure is the right one until you reach the front), by joining the queue for window number one, a window that was marked “No Barriers”. The experienced China-traveller may well chuckle at the idea, but in this case the description was literal rather than philosophical. Usually heavy-duty stainless steel railings ensure queues remain queues at Chinese railway ticket offices, and this was the case for the dozen or so other windows, with around fifty people queuing for each of them. Perhaps the lack of crowd control infrastructure had blinded these would-be travellers to the fact that there were only three people waiting at window number one. Although I wasn’t absolutely sure it was at the right window to buy the ticket I wanted, I was feeling smug at my achievement of being fourth in line to be served within a couple of minutes of arriving.

The smugness had been wiped from my face by the time I left the window, despite the fact that I had a ticket to my destination, and had received exceptional customer service from the English-speaking staff member. The problem was not simply that there were no soft-sleeper berths available, but neither were there any hard-sleepers, nor, indeed, even any seats. I’d made an on-the-spot decision to take a gamble that I would be able to secure a berth once on the train.

Unlike the gamble that window number one would sell the ticket I wanted, my gamble that I would secure a berth on the train didn’t pay off. My only choice was to sit on a vacant seat until someone with a reservation for that seat moved me on. It was an hour and a half into the journey that I got a seat. I sat down, a niggling thought at the back of my mind that maybe, perhaps, just possibly the decision to take the train was less than inspired!

Three hours later I was ‘moved on’, and found a seat among a group of men from Shandong. They were jovial, their banter switching between Mandarin and a dialect I did not recognise. A short phone conversation in English was to set me apart, the foreigner in their midst. Their reaction was typically Chinese in as much as they assumed I spoke no Chinese but were insistent on communicating non-verbally through smiles and nods and the periodic silent offering of fruit, a drink, sunflower or pumpkin seeds. All silently but deferentially declined, but each encounter an affirmation of unspoken friendship.

I was fortunate in as much as I wasn’t ‘moved on’ for the period during which we all slept – as much as anyone sleeps on a train. But sure enough the morning brought new travellers and when my inevitable move came it was among the confusion of this group also being uprooted, not because they did not have reserved seats, but because they had swopped seats to sit together. One asked another what number seat I had, realising it wasn’t the one I was sitting in. They were slightly surprised when I replied in Mandarin that I didn’t have a seat reservation. One pointed and said, “sit here”, but I had my next survival trick for the seatless ready and said I was going to get breakfast, and made my way to the dining car, my home for the next hour and a half.

When I returned to where I had been previously, and where my luggage still was, I was greeted by smiles, and offered a seat (the train was once again full with a few standing), an offer I politely refused. Eventually though, a seat became available and I took it. For some time we exchanged pleasantries, the usual questions and praise for speaking “really good” Mandarin. On the latter I had to disagree, not out of any sense of cultural necessity or false modesty, but in all honesty my Mandarin could only be described as “really good” if it was preceded by the word, “isn’t”.

I really felt an affinity with these men. They reminded me so very much of some of the accounts of the men of the Chinese Labour Corps, all the more so because of this long train journey, though undoubtedly we were enjoying far more comfort than the recruits did as they travelled by train for six days across Canada.

On my next eviction one of the men told me to sit in a particular seat that someone was getting up from. The person wasn’t leaving, he was one of this group of friends. The man who had told me to sit in the seat was a cheerful chappy, a smile almost constantly on his face, physically of stereotypical stocky Shandong build that had made the recruits of the Chinese Labour Corps such an excellent choice for the tasks they faced on the Western Front. As I sat down he leaned over and said, “this is my seat, you won’t have to move again.” With that he turned away.

What followed was somewhat embarrassing, for no matter how much I tried to give the seat back there was insistence that I remain where I was, even when my kind friend was himself standing because there were no seats. I was reminded of a passage I had read in Daryly Klein’s account of the recruitment of Chinese labourers in Shandong:

“To-day four companies, i.e. close on 2000 men, passed through the doctor’s hands. It was final examination day. Every coolie is medically re-examined a few days before departure. About 6 per cent were rejected entirely owing to eye troubles. At sunset this 6 per cent stood a little apart from their successful mates ; in the shadow of the familiar chimney they stood disconsolately expectant, keenly enough aware of their fate, asking one another helplessly why the light of the new life was suddenly extinguished, why they had to return to the old meagre struggle for existence, why they should be made to lose face with their kinsmen and fellow-villagers, just because the lids of their eyes were inflamed. They were to be sent home by to-night’s train ; and the happy others, knowing this, went up to them, when their officer’s eye was turned the other way, and gave them each a few coppers, at the same time bidding them farewell.”

I remained in that seat until the end of my journey. I should say these men had no idea who I was or the purpose of my visit to Shandong when they were being so very kind. About ten minutes before they got off the train (forty minutes before I was to get to Shenzhen) I ended up showing my new friend the campaign video, explaining why I was in Shandong. He was clearly aware of the story, and shook my hand with genuine warmth and spoke the only English words I heard any of them speak, with a broad smile he said, “very good”.

My train journey was unpleasant in so many ways, from the overcrowding to the awful breakfast in the dinning car. And yet I do not regret the decision to take the train. Memories of discomfort and lack of sleep fade compared to the experience of meeting those men of Shandong and getting a very real insight into their generosity of spirit, good humour and friendliness. I felt in a very real way that I had somehow met the spirit of the men of the Chinese Labour Corps.